Dean White Shares 'A Note on Juneteenth'

"You can't give me the right to be a human being. I'm born with it," said an elderly, formerly enslaved man to the White folklorist and radio show host John Henry Faulk.

Faulk had been explaining to the man “what a different kind of White man I was,” telling the older gentleman that he was in favor of giving Black people civil rights and giving them access to education and giving them any job for which they were qualified. Faulk admitted to initially being stunned and angered by the elder’s retort. Although Faulk had an epiphany in that moment, namely that the old man was correct and that being an ally meant fighting the social restrictions to this natural right, many Americans still suffer from the disease of privilege that plagued Faulk. Significantly, Juneteenth is an exploded manifestation of that same, simple eloquence that an open mind can learn from but that the privileged wish to silence.

Juneteenth is a subversive celebration because it centers the experiences of the formerly enslaved instead of social and political elites. Just as importantly, Juneteenth illuminates the wicked alchemy of White Supremacy. When Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas in June 1865 to declare that the American Civil War was over and that all slaves were free, they did so three years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and months since the seditionist Confederacy had surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia. Moreover, it was countless years and months after thousands of enslaved Black people had fled to Mexico to try to create freedom for themselves. Some scholars estimate that as many as 10,000 enslaved people used this southern route of the Underground Railroad to escape American Exceptionalism. After all, Mexico had outlawed slavery in 1829, a fact that angered the White slave-owning settlers who had moved into its northern province of Texas. It does not take much imagination to see that spirit of liberty fanning the Mexican resistance to the French-imposed emperor, Maximillian (a member of the Habsburg royalty), who came to power during our deadly, internecine conflict. Black people supported the resistance and as the military tide turned against the emperor, he invited ex-Confederates to move to Mexico as a way of shoring up his position. When the Liberal forces of President Benito Juarez and General Porfirio Diaz captured Maximillian, they executed him, interestingly enough, on Juneteenth 1867.

In my hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee, we did not grow up celebrating Juneteenth because August 8th was our “Emancipation Day:” the day that future president Andrew Johnson freed his slaves in East Tennessee. Over time, Juneteenth and other Emancipation Days grew into more than a celebration of the past. They became platforms for Black economic and cultural expression, for exercises in bodily autonomy nearly unthinkable on any other day of the year. In addition, some Emancipation Days became venues for labor and political organizing, especially when doing so in plain sight might get you killed. More recently, the push to have Juneteenth recognized as a holiday is as much about compelling all Americans to acknowledge the long road ahead of us, as well as grappling with the sinful past behind us. UVA Press’s new book series “The Black Soldier in War and Society,” which I co-edit with Le’Trice Donaldson, serves a similar purpose, albeit on a smaller scale.

The end of American slavery was not freedom; it was simply the termination of one type of bondage. The works that will appear in our book series will reflect the ongoing and multifaceted quest for freedom as demonstrated by Black people who wore the uniform of the United States military, the experiences of the families of service members, and the ways that all of them fought—and keep fighting—for justice in their communities. Since millions of our fellow citizens remain willing to drum up ghosts and rely on irrational fears of exaggerated threats to deny us the many exercises of our freedoms, our book series is both timely and will be in keeping with the unadorned defiance of an old freedman: “You can’t give me the right to be a human being. I’m born with it.”

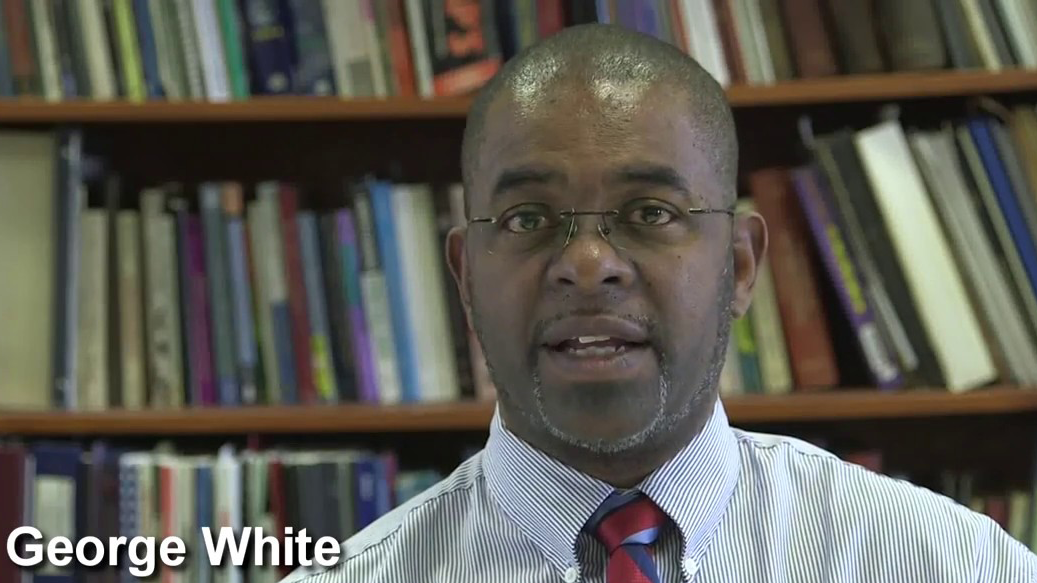

George White, jr. (co-editor) Professor of History and Interim Dean School of Arts & Sciences York College, CUNY

Le’Trice Donaldson (co-editor) Associate Professor of History Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Revised: June 22, 2022